Tatting is ideal breakfast-time reading, a book to prop between the coffee pot and the marmalade jar (attested by the butter stains that now adorn my copy, which was kindly sent to me by its publisher, Handheld Press). Lively, affectionate, rich in atmosphere and offering jolts of sharp humour, it is a delicious escape into an Edwardian world of silver kettles and strawberries, champagne and charm.

Faith Compton Mackenzie’s novella opens in London, dropping us straight into story and scene before moving, via a journey spent in well-judged exploration of character and backstory (and who among us has not found their mind wandering over past events while travelling in a railway carriage) to an irresistibly fey Cornwall of enchanted pools, plump rain, and gently subversive domestic servants. This is the Cornwall of incomers, not the local people with whom they are inevitably at mystified and mystifying odds: the high Anglo-Catholic priest, Father St John; Miss Josephine Want, his possessive and determined acolyte; Guy Mallory, poet-turned-lay preacher; Guy’s new wife, the blithely self-possessed Laura; and the impoverished Irish artist, Ariadne Berden. The naming of these characters is worthy of Dickens. Father St John is preaching his brand of religion in a Noncoformist wilderness, Miss Want, so lacking in empathy or self-awareness, craves things that life will never give her, and Ariadne Berden is that most cunning of creatures, the charity case who by conspicuously resisting charity achieves the feat of resting heavily upon the collective conscience of her small circle.

Compton Mackenzie is a beguiling guide to the inward and outward lives of her protagonists, and appears to have had immense fun in her narrative role, drawing closely and playfully upon her own Cornish experiences as a real-life Laura, married to the writer and lay preacher ‘Monty’ Compton Mackenzie (of Whisky Galore fame).

She need not waste time trying to understand Father St John. She was convinced that there would be no difficulty in their relationship. It would surely be amusing and peculiar — just what she liked.

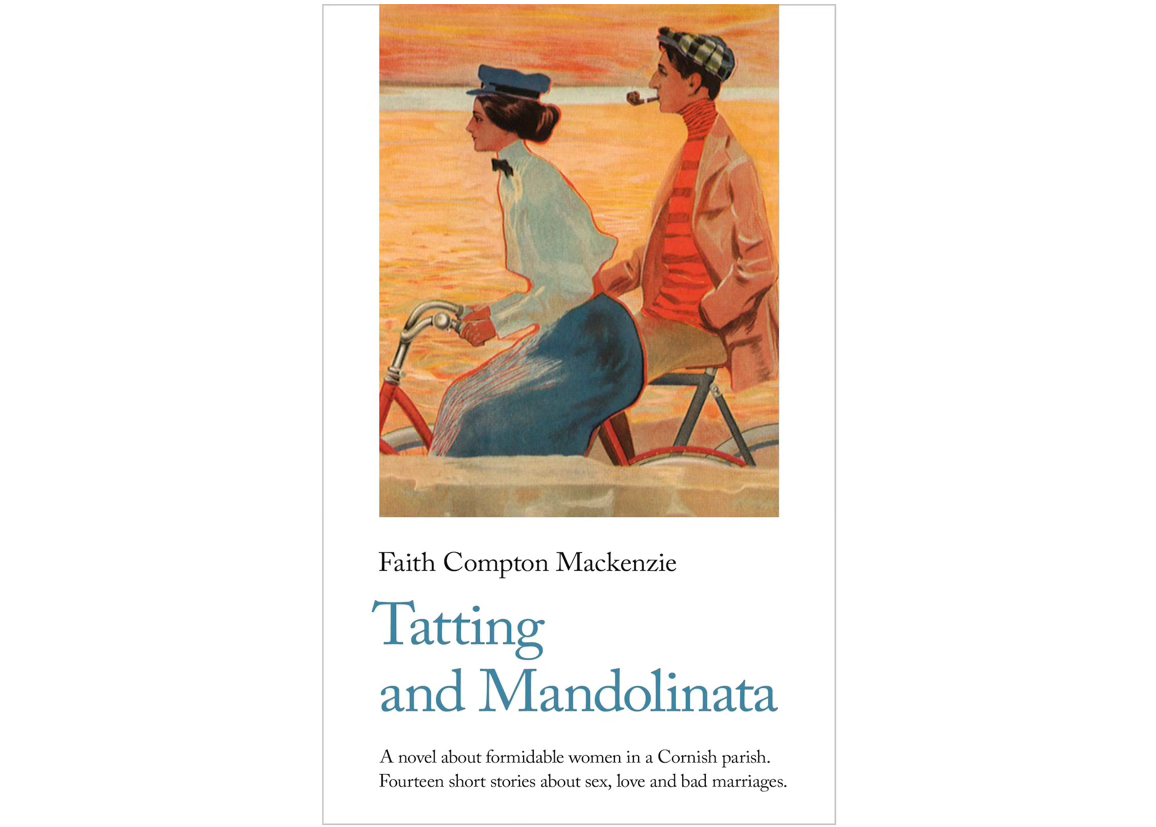

Faith Compton Mackenzie

Tatting contains strangeness among the sweetness, too, an incongruity of tough granite and delicate sea pinks that is entirely Cornish. Indeed, a walk to admire those very flowers beside a clifftop path feels like a prelude to something much darker, so that I had to read the twist twice. There is a wreckers’ undertow to events — a series of poison pen letters, an unexplained gunshot — that mars the eccentric equanimity of the vicarage household, until all (or perhaps not quite all) is tied neatly into the story’s conclusion.

How apt that tatting (a decorative craft, similar to crochet) is known in France as frivoloté.

If Tatting seems to be a morning book, the tales collected within Mandolinata belong emphatically to long, hot afternoons. These are stories to experience on a couch or divan, a breeze stirring gauzy voiles at the windows and the louvred shutters casting slatted sunlight onto the floor. And even if you cannot experience such an afternoon in fact, you will certainly do so in the fiction of these fourteen short stories, and particularly in the opening sequence set in the little Magna Graecia city of Spiaggia (literally, ‘Beach’), with its constant carnival of visitors passing lightly over the white stones, through the sparkling waves and down the smoke-green olive groves, trailing love, sorrow, envy and a particular brand of vulnerable contentment in their wake.

That’s how it was in Spiaggia. Something flashed and was gone. Hardly a memory — so uncertain and eventful was life in that little city of pleasure. They went, and forgot, and you stayed — and forgot, because something else always happened so quickly.

Faith Compton Mackenzie

Hedonistic, melancholic, always involving, Compton Mackenzie’s stories ‘in the style of Chekhov and Katherine Mansfield’ (as she herself noted in the three-volume memoir I am now eager to read in full), are often also charged with a sly and good-natured eroticism, most graphically in the case of the spinster Miss Mabel Ebony, yet another of her sublimely-named characters. Ebony wood is incredibly hard and unbending, so dense that it will sink in water: after an encounter with an amorous boatman, Miss Ebony is able to give only ‘a fluttering attention to the wild beauty of the garden in a cleft of the sheer cliff and the huge limestone column that dominated it,’ whilst the perspicacious hostess-gardener sends up a prayer to the lusty deity of that same rock on her guest’s behalf (‘Variations on a Theme: Miss Mabel Ebony’).

Like other writers before and since, Compton Mackenzie recognised and embraced the emotional and physical allure, the intoxication and seduction, of Italy, yet also remained somewhat remote and analytical, as close observers of human nature must.

The dramatic quality of the scene, the magic of those moonlit or starry nights are enough to overwhelm the stoutest heart, but with the tumult of bygone festivals, orgies and saturnalia still raging, what hope is there of escape for any one?

Faith Compton Mackenzie

Further stories take place in Rome, France and England. Our regret at leaving Spiaggia is short-lived, for the mood is sustained, both jewel-like and ethereal. Yet I gained the sense that Compton Mackenzie was missing the fictional Italian town of her own imagination, which was based upon the home which she and ‘Monty’ had shared on Capri. For though the England-set stories are just as perceptive, just as skilful, they carry a recurring impression of greyness — a monstrous sock to be darned, a seafront parade of houses, even a family named Grey — which conveys a perceived existence in England as the dull obverse to life beside the glittering azzurro of the Tyrrhenian Sea.

I have a chequered history with the short story form, dating back to an early comprehension exercise built around Katherine Mansfield’s ‘The Garden Party’ which focused purely upon sentence structure, simile and metaphor (‘Jose, the butterfly — discuss’) rather than the overarching revelatory theme, as part of an English curriculum which offered no room for experiencing the whole story, much less the discoveries to be made within both the text and ourselves. There was no ignition of passion, or even curiosity, and it was a long, long time before I mustered the will to read ‘The Garden Party’ for myself alone.1

The short story was introduced to me as little more than an academic exercise, language as arithmetic, and too many of the stories I have read since then have approached the form in a similar systematic vein, going through the motions whilst attempting simultaneously to be ‘clever’.2 There is a right way to wrong-step the reader, and my experience is that many short story writers fall wide of the mark. Spotting the ‘cleverness’ of these writers is akin to identifying how a magician performs a magic trick — the story, and the trick, become meaningless. ‘The Garden Party’ is a divine example of how to entertain whilst also making a reader think. Mansfield had no interest in adopting the shock tactics which so many writers employ in place of the elusive magic. We are disturbed because Mansfield’s Laura — a character whose experience of the world she has led us carefully to share and understand — is disturbed, not because Mansfield has bludgeoned us into it.

White figures in the dusk; our cigarettes like fireflies; we sat silent for a moment while somewhere near Destiny stirred.

Faith Compton Mackenzie

For me, the short story should be a thing of nuance, and Compton Mackenzie achieved exactly that, over and over again, in Mandolinata. ‘The Writing Case’ gives the impression of being one of her own childhood memories, spun into an act of quiet female rebellion which grown women could still learn from today. ‘With Custody of the Child’ reads as a reaction to the stark reporting of the matrimonial cases that appeared in her morning Times with the hollow persistence of a tolling bell. There are occasional intimations of war (‘Le Bonne Mine’), but mostly what I found here were intimations of sadness. The tragedy of the title story, ‘Mandolinata,’ based shockingly on fact, the telling social comment of ‘The Unattainable,’ so brief, yet perfectly formed, and the heartbreakingly chilly conclusion of ‘The Children of God’ are deeply affecting, but even Compton Mackenzie’s happy endings seem built upon exquisite, eggshell joy. Marriages founder, lovers reunite with their relationships still curiously restless and in question, victories appear hauntingly transient and fragile. In her stories, as in Spiaggia, as with the face of the sea itself, everything is in a state of constant change.

He sat down and looked out over the vineyard and olive orchard that he wished were his — over the orchard to the great mountain which wore the bloom of a purple plum against the dense blue sky.

Faith Compton Mackenzie

Faith Compton Mackenzie’s narrative voice is ever-present, strong but never strident. Coupled with her eye for description, and particularly the description of place, weather and mood, it recalls the literary style of Sylvia Townsend Warner (a comparison which drew me to this book almost immediately after reading the astonishing The Corner That Held Them). Meanwhile, her reflections upon Father St John, the Anglican Mass and deeper questions of private spirituality put me in mind of dear Rose Macaulay, and the satirical soul-searching of The Towers of Trebizond in particular. I value the symmetry of this: both Warner and Macaulay feature prominently among the titles reissued by Handheld Press. It is immensely sad that the Press has now ceased publishing, albeit with a catalogue and legacy of rediscovered literature (and consistently on-point introductions) of which they should be justly proud. Their very last title, The Gulls Fly Inland, is out this month and I will be reviewing it here in due course. Handheld themselves will continue selling stories until next summer. I predict that the second-hand trade in their carefully curated, distinctively-bound titles will be both brisk and competitive. Catch them while you can.

© The Unhurried Reader 2024

My anger and regret at the way I was taught ‘Eng. Lit.’ at school, the years, scope and depth of reading — and thus the opportunities — that I lost because of it, is a polemic for another day.

Honourable exceptions include Compton Mackenzie’s twin muses and, of course, Virginia Woolf.

What an absolute jewel of a review. Thank you for this which has brightened a turgid day.

This sounds an absolute delight - thank you!